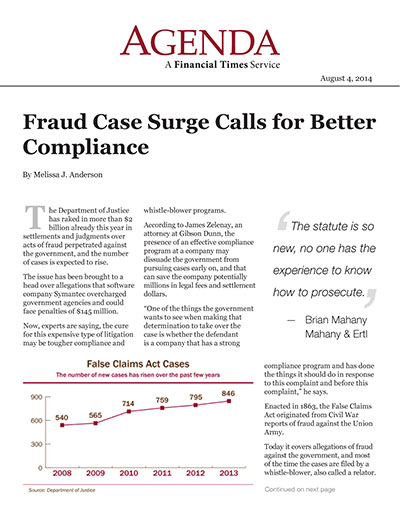

The Department of Justice has raked in more than $2 billion already this year in settlements and judgments over acts of fraud perpetrated against the government, and the number of cases is expected to rise.

The issue has been brought to a head over allegations that software company Symantec overcharged government agencies and could face penalties of $145 million.

Now, experts are saying, the cure for this expensive type of litigation may be tougher compliance and whistle-blower programs.

According to James Zelenay, an attorney at Gibson Dunn, the presence of an effective compliance program at a company may dissuade the government from pursuing cases early on, and that can save the company potentially millions in legal fees and settlement dollars.

“One of the things the government wants to see when making that determination to take over the case is whether the defendant is a company that has a strong compliance program and has done the things it should do in response to this complaint and before this complaint,” he says.

Enacted in 1863, the False Claims Act originated from Civil War reports of fraud against the Union Army.

Today it covers allegations of fraud against the government, and most of the time the cases are filed by a whistle-blower, also called a relator.

These accounted for 89% of the 852 new cases filed in 2013 and are known as qui tam cases.

The government is given the opportunity to join the whistle-blower as a defendant following an investigation of their claims. Whistle-blowers are entitled to up to 25% of settlement or judgment amounts if the government joins the case, and 30% if it doesn’t. By the DOJ’s statistics, the government is successful in 95% of the cases it joins.

But it is selective. The government joins about only a quarter of qui tam cases. When it declines to participate, the success rate for the defendant plummets to 9%.

That’s why, Zelenay says, the first stages of a case are so critical.

“The first three to four months when a False Claims Act case is being filed, that’s the period of time when the government is making its determination whether or not to take over the case,” he says.

If a company has a strong compliance program, it may have less to worry about when the DOJ’s investigators come around, says David Kwok, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center.

“The good thing about this is that this dovetails nicely with what the company has to do with compliance, anyway,” he says, suggesting that ongoing training and auditing can help companies steer clear of False Claims Act charges.

“It’s not just an issue of training, but verifying what is going on in the field,” he says.

Whistle-Blowers

On July 18, the DOJ announced it was intervening in a case against the software company Symantec, which a whistle-blower, Lori Morsell, says overcharged government agencies for its computer software. The company could be on the hook for $145 million in penalties.

According to Morsell, she learned in her role at the company overseeing government sales contracts that some longtime corporate customers were receiving significant discounts — much deeper than the company had reported when negotiating its government deals — and, after investigating, she reported the issue to her supervisor and the compliance department.

The court filing says, “over time, Morsell realized that Symantec did not have the culture or systems in place to allow her to bring Symantec into compliance.”

Whistle-blower plaintiffs and their attorneys say the link between culture and compliance is critical. Often whistle-blowers bring a False Claims Act suit after their internal complaints have been rebuffed, they say, and sometimes other issues are at stake too.

“From my perspective representing whistle-blowers, companies and boards should make it a top priority to treat employee complaints fairly and take them seriously,” says Joy Clairmont, a shareholder in the whistle-blower, qui tam and False Claims Act group at the law firm Berger & Montague.

“I’ve had many people who, working inside a company, complain about something, and it’s not necessarily the fraud underlying the False Claims Act action; it’s something else. And the company ignores their complaints or retaliates against them, and this motivates them to report other types of fraud and bring a False Claims Act suit.”

Whistle-blowers also report issues with compliance hotlines, Clairmont says. Sometimes there is a perception that they are not truly anonymous. And according to David Danon, a former attorney at Vanguard and whistle-blower in a False Claims Act suit against the firm announced in July, a whistle-blower complaint may indicate other problems throughout the company as well.

“By the time somebody feels they have a claim, it’s probably too late. If the culture is such that there’s already a significant violation, chances are it’s not going to be managed well,” says Danon, who believes he was fired for reporting the issues internally first.

The government declined to intervene in Danon’s case. His attorney, Brian Mahany, of Mahany & Ertl, says that’s because of its unusual nature. Danon’s case asserts that Vanguard developed a unique business structure to avoid paying millions of dollars in taxes. The federal government does not accept False Claims Act cases on the basis of unpaid taxes, so the case is filed in the state of New York, which does. But, Mahany says, New York has argued few, if any, cases like this one.

“The statute is so new, no one has the experience to know how to prosecute,” he says.

A Vanguard spokesperson declined to participate in an interview, but says in an e-mail, “We believe that this case is without merit, and we intend to defend the matter vigorously.”

A company may not even know it is subject to a claim until the government announces whether it will intervene or not, although there are telltale signs.

“Sometimes the defendant receives a subpoena from its government regulator or the Department of Justice, or there are strange statements being said by employees during an exit interview, or suddenly there’s a lot of scuttlebutt on websites or former employees start getting contacted,” Zelenay says.

Symantec first disclosed the investigation by the DOJ in a 10-Q filed in July of 2012.

“It is possible that the investigation could lead to claims or findings of violations of the False Claims Act in connection with our [government] contracting activity. Violations of the False Claims Act could result in the imposition of damages, including up to treble damages, plus civil penalties in some cases,” the filing says.

In an e-mail, a spokesperson for Symantec says, “We have fully cooperated with the government throughout its investigation, which Symantec was alerted to and first publicly disclosed in June 2012. We deny any wrongdoing and are confident the prices paid by the government for Symantec products and services were fair and reasonable.”

Robert Fletcher, a shareholder at the law firm LeClair Ryan, says companies and boards of directors are well advised to cooperate with government investigations.

“Some companies in the past have taken a tactic of stonewalling the government, and in my experience that has never worked out well,” he says.

“If you can be responsive to the government and show you have nothing to hide and you are going to work with them, I think that goes a long way to heading things off and ultimately minimizing the expense of these kinds of claims.”

Fletcher has noticed another new pattern in False Claims Act litigation that may be disturbing to boards.

“Recently there’s been a trend to try to expand the scope of the claims made against individual officers and directors,” he says, describing a case with a medical billing company, in which the government wasn’t happy with the settlement terms offered by his firm and came back with an expanded claim, naming the president and CEO.

“The government is getting much more aggressive,” he says.