Not long ago the oil industry looked like it had dodged a bullet. After the worst bust in a generation cut crude prices from $100 a barrel last summer to $43 in March, the oil market rallied. By June, prices were up 40 percent, passing $60 for the first time since December. Oil companies that had cut costs began planning to deploy more rigs and drill more wells. “We didn’t think we’d be quite this good,” Stephen Chazen, chief executive officer of Occidental Petroleum, told analysts in May.

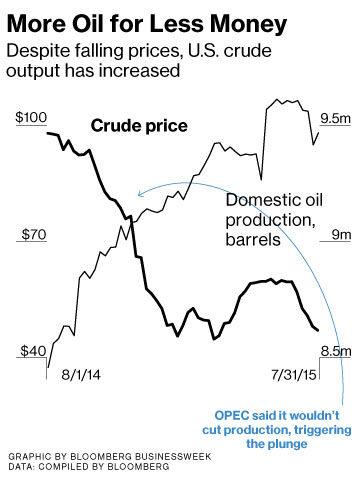

The runup was short-lived. Fears over weak demand from China, along with rising production in the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and Iraq pushed prices back below $50. In July, even as the summer driving season boosted U.S. gasoline demand close to record highs, oil posted its biggest monthly drop since October 2008. “The much feared double-dip is here,” Francisco Blanch, head of global commodity research at Bank of America, wrote in a July 28 report.

The largest oil companies are reporting their worst results in years. ExxonMobil’s second-quarter net income fell 52 percent; Chevron’s fell 90 percent. ConocoPhillips lost $180 million. Billions of dollars in capital spending have been cut, and more layoffs are likely. Part of the problem facing the majors is that they’re producing in some of the most expensive places on earth: deep water and the Arctic.

With their healthy cash reserves the majors can hold out for higher prices, even if they’re years away. The same can’t be said for many of the smaller companies drilling in the U.S. shale patch. Shale producers had bought themselves time by cutting costs, locking in higher prices with oil derivatives, and raising billions from big banks and investors. Many cut drilling costs by as much as 30 percent, fired thousands of workers, and renegotiated contracts with oilfield service companies. “That postponed the day of reckoning,” says Carl Tricoli, co-founder of private equity firm Denham Capital Management.

But it’s not clear what’s left to cut. The futures contracts and other swaps and options they bought last year as insurance against falling prices are beginning to expire. During the first quarter, U.S. producers earned $3.7 billion from these hedges, crucial revenue for companies that often outspend their cash flow. “A year ago, you could hedge at $85 to $90, and now it’s in the low $60s,” says Chris Lang, a senior vice president with Asset Risk Management, a hedging adviser for oil companies. “Next year it’s really going to come to a head.”

Over the first half of 2015, U.S. shale producers were able to raise about $44 billion in debt and equity, according to UBS. As oil prices keep falling, investors are losing their appetite for risky shale debt. Bonds have become more expensive and are laden with more onerous terms, including liens against drillers’ oil and gas assets. More than $24 billion of the $235 billion in debt owed by 62 North American independent oil companies is trading at distressed levels, meaning their yields are more than 10 percentage points above U.S. Treasuries.

“For the weaker companies, it could be very, very painful. Some of them are essentially running on fumes.”

—Jimmy Vallee, Paul Hastings

Regulators have warned of the risks of lending to U.S. shale drillers, threatening a cash crunch in an industry that’s more dependent than ever on other people’s money. In October, as they do twice every year, banks will reevaulate drillers’ lines of credit, which are often based on the value of reserves. If prices stay where they are, many companies could be cut off from crucial funding. “For the weaker companies, it could be very, very painful,” says Jimmy Vallee, a partner in the energy mergers and acquisitions practice at law firm Paul Hastings in Houston. “Some of them are essentially running on fumes.”

Over the past year, shale producers have lowered their costs so much that the average break-even price for a barrel of U.S. crude is now in the upper $40s, down from $60, according to research from IHS Energy. That’s allowed them to keep producing, feeding the glut that continues to weigh down prices. At some point, though, they may have to pull back.

The bottom line: The renewed decline in oil prices has made it hard for shale producers to issue stock or sell bonds.