Excerpt: California: State of Collusion by Joseph Tully

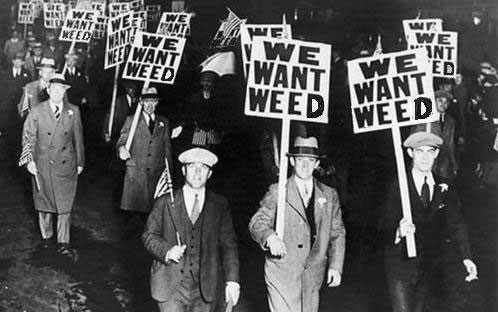

The History of Cannabis Prohibition

The Grapes of Wrath

The agricultural wealth of California is renowned. In the 1920s, California was the nation’s leading agricultural state, as it continues to be to this day. Grapes were a very important part of the state’s economy during this period.

In fact, by 1919, California produced 80 percent of the country’s grapes. Fifty years later, cannabis would begin its path toward becoming a $14-billion-dollar industry in the state. Prohibition would prove impossible to effectively implement for alcohol and cannabis when California’s economy depended on the production of both.

The Napa wine industry was just beginning to take off at the start of Prohibition, and though the ban nearly wiped out the wine industry, it had a reverse effect on the grape growers in the state. Prohibition prevented the commercial production and distribution of alcohol, but it did allow for the growing of grapes as well as home, medicinal, and sacramental wine production.

Wine sales plummeted, while grape sales skyrocketed. one reason for this was the wide-scale distribution of wine bricks, condensed grapes that could be dissolved in a gallon of water and fermented. Estimates calculate that home winemaking grew nine times over during Prohibition, largely due to the distribution of wine bricks from coast to coast.

Many well-known wineries of today, including Beaulieu vineyards and Beringer winery, were allowed to stay open during Prohibition under the guise of producing sacramental wine. Still, other wineries hid illegal wine production behind new fields of prunes, peaches, and other fruits planted where acres of grape vineyards had once stood.

The success of grape production in California during Prohibition mirrors the prohibition of cannabis in the 1970s, when California marijuana began its rise to popularity, and up to today. In fact, our own federal government can take an immense amount of credit for driving the popularity of California-grown marijuana past the previously more popular Latin American varietals like Acapulco Gold and Panama Red. At the time, the U.S. government sponsored a controversial program to spray Mexico’s booming marijuana crops with the herbicide paraquat.

Instead of deterring Americans from smoking marijuana for fear of illness from the toxic paraquat, the program simply drove them to homegrown alternative sources. False claims of death and disease caused by smoking paraquat-contaminated Mexican weed spread like wildfire.

By the time the paraquat program was halted in 1979, roughly 35 percent of marijuana smoked in California was grown locally. By 2010, it’s estimated that 79 percent of pot smoked in the entire U.S. was grown in the Golden State.

Commercial sale of cannabis was illegal, but agricultural production boomed. People grew it on their secret farms, in closets, hidden forests, and backyard gardens. Medicinal marijuana is a part of the consumption, but the majority is consumed illicitly, purely for recreational use—just as grapes were during prohibition.

There’s no doubt that agriculture is an important part of the California economy, and a reason it continues to act like an unsupervised teenager, eschewing federal governance at will. According to the USDA, California agriculture is a $46.5-billion-dollar industry, and it’s estimated to generate at least $100 billion in additional, related economic activity.

While almonds ($5.8 billion) edged out grapes ($5.6 billion) as California’s largest legal cash crop, many estimates place the state’s marijuana production at far more than almonds and grapes combined.

According to a 2006 report published in The Bulletin of Cannabis Reform and prepared by Jon Gettman, Ph.D.; the former head of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), the country’s annual marijuana production was then valued at nearly $36 billion, with California responsible for more than one-third of that value, or $14 billion.

A 2012 book, Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know, written by experts from Pepperdine and UCLA, among others, disputed these figures. The 2012 book estimates the total value of the crop at $2.1 to $4.3 billion, still a significant value, but they also admit that any estimate is unreliable as much of the production and distribution occurs out of sight.

With so much of the economy invested in weed and grapes, you can imagine that local California authorities would have a different view of enforcement than federal authorities.

Law of Supply and Demand

When a product is prohibited, the demand for it does not cease. The risk of producing and delivering a contraband finished product increases, as do the costs of production. The prohibition of alcohol was not a problem for rich white people who could afford to continue consumption. The laws were meant to control drinking by poor ethnic immigrants and other minorities including poor blacks, both urban and rural. Racists could have a champagne toast to the success of prohibition.

This gave rise to bootleggers and speakeasies providing alcohol. Ships brought liquor barrels down from Canada and unloaded them on the hundreds of miles of beaches along the California coast. Beer and booze ran up from Mexico. While prohibition was a Federal law, the local authorities saw it as an opportunity to control, regulate, and profit from this black-market industry.

According to the LA Times, the prohibition-era head of the LAPD vice detail (“The Purity Squad”), ran gambling joints on the side and then quit to become a bootlegger. Mob boss Charles Crawford even boasted of a private telephone line into LA’s City Hall.

Daniel Okrent, the author of Last Call, a book on the rise and fall of Prohibition, sums up the situation in the Bay area concisely: “In San francisco, Prohibition was only a rumor.” In 1920, the democratic Party held its national convention in San Francisco, and Mayor Sunny Jim Rolph furnished every delegate with a bottle of whiskey, delivered to their hotel rooms.

In 1922, there were approximately 1,492 speakeasies in San Francisco, which spoke volumes about the 83 percent of San Franciscans who did not vote for Prohibition, reports Ellen Gorchoff-Fey on San Francisco City Guides.

While the rich and elites drank imported whiskey in swank underground clubs, the poor went dry, paid too much for inferior liquor, or worse, went blind drinking homemade alcohol contaminated with methyl alcohol.

The prohibition of marijuana made its street price increase, and the reward for growing it very lucrative. But the illicit retail business for cannabis was much sketchier than the speakeasies. The rich could afford quality marijuana from a trusted source.

Hollywood and hippies seemed to have an abundance of pot in the ‘70s. it was almost part of the California culture. But at the street level, tainted or fake marijuana was a risk.

Even today, with marijuana laws loosening, we see people poisoning themselves with chemicals marketed as “air freshener” or “spice,” which are toxic, cooked-up artificial cannabinoids. Prohibition is an artificial skewing of the marketplace that leads to crime, fraud, and racism. Legalization brings equality to the marketplace and allows everyone safe, affordable access.